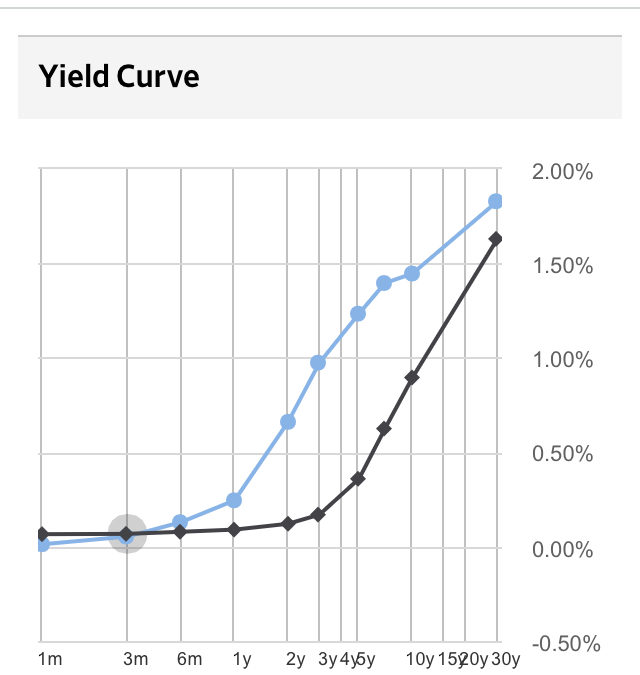

Like many, I belatedly came across the Nomad Investment Partnership letters this past year. Nick Sleep’s idea of an equity yield curve rings true to me and is consistent with my experience.

For those unfamiliar, the idea is that “patience has a value, and that returns increase with time in the equity market as they do on a normal bond market yield curve. In the bond market the higher yield is there to compensate for the increase in risk that the principal will not be repaid, or that the principal may be devalued by inflation. That is not how it works in the equity market: in our opinion business outcomes can be more predictable several years out than they are in the near term.”

Consider the difference between returns in merger arbitrage vs. liquidations. I know a few great merger arb investors that are thrilled with 8-9% annual returns and I know a few liquidation investors that put up high teens annual returns (higher if I’m being honest). Both groups are smart, but the liquidation investors (those going further out on the equity yield curve) are playing an easier game. Arguably the merger arb investors are harder working as they have to constantly monitor the performance of their ideas while investors in liquidations need only find a handful of good ideas a year.

Their time frames vary. While liquidations might unfold over 24-36 months, merger arbs (that don’t require regulatory approval) typically take less than a year to play out. Merger arb investments that produce higher returns tend to take longer than average, and therefore are further out on the equity yield curve. This happens when a bidding war for a target ensues or when there is additional contingent compensation to be paid post close should various targets/approvals etc. happen. Not surprisingly when contingent compensation is offered, the merger takes on characteristics akin to a liquidation as there are multiple liquidity events rather than just one.

Sleep emphasizes patience as the determinant of how far out you are on an equity yield curve. I think about patience along two dimensions:

- How long we hold an investment

- How long we wait for that investment to begin returning capital to us

How might you push yourself out on the equity yield curve in private markets like commercial real estate?

- By owning assets with considerable optionality such as those that resemble convertible bonds (including “covered land plays”). Here’s a Twitter thread on convertible bonds in real estate if you want to hear more. Owning real estate with considerable embedded options is critical because real estate’s base case returns on capital just aren’t that sexy [Click to Tweet]. Increasingly I find direct and indirect ownership of non-depreciable real estate interesting. My take is that investors typically overpay for real estate’s depreciation benefits & therefore underpay for real estate that lacks depreciation benefits.

- By owning assets that require reinvestment of cash flows into the business prior to distributing any capital to shareholders/LPs etc. Think, taking on lease up risk, repositioning assets etc.

Since COVID began my partners and I have almost exclusively been funding short term performing first mortgages. We’re literally on the front of a yield curve! How might I push us further out the private mortgage yield curve while being overcompensated for the risks Sleep points out (namely inflation)?

- I’m in the process of building deal flow to purchase seller-financed notes. Here’s a recent Twitter thread with an example. Imagine a person sells her property and plays the role of the bank and carries a loan. These loans tend to be longer term and (unfortunately) tend to be owner occupied properties–another risk to consider. But, I can purchase them as performing notes with an in place yield at a discount to their payoffs. Should the property sell or be refinanced, in addition to their in place yield (portfolio income), this prepayment creates a capital gain kicker enhancing the return. A prepayment isn’t 100% guaranteed and the timing of such a prepayment, is of course, uncertain—with secondary market purchases of seller financed notes we’re WAY out on the equity yield curve.

- Purchasing non-performing mortgages where I’m paid to work out the loan. I’ve done this before and will likely do it again.

Did you enjoy this article? You can share on Twitter by clicking HERE

Recent Comments